(From the text of the same title of the author)

“The longest trip is the inner journey” Dag Hammarskjöld

Before we start doing specific exercises, we need to consider the nature of loneliness and its place in contemplative practice. In addition, we will deal with the ethical foundation of meditation, which is essential for proper orientation towards the contemplative path. With these preliminaries we can then turn to the diversity of practices, first those that are designed to underpin our psychological health and secondly those that direct our inner gaze beyond oneself. We will move forward by establishing humility and reverence as fundamental attitudes for the cultivation of inner harmony, emotional balance and attention. With these objectives achieved we can assume the altruistic work of meditation and contemplative research whose fruits can be useful to us and others.

Before we start doing specific exercises, we need to consider the nature of loneliness and its place in contemplative practice. In addition, we will deal with the ethical foundation of meditation, which is essential for proper orientation towards the contemplative path. With these preliminaries we can then turn to the diversity of practices, first those that are designed to underpin our psychological health and secondly those that direct our inner gaze beyond oneself. We will move forward by establishing humility and reverence as fundamental attitudes for the cultivation of inner harmony, emotional balance and attention. With these objectives achieved we can assume the altruistic work of meditation and contemplative research whose fruits can be useful to us and others.

This chapter will provide a brief overview of the path as I understand it. Consider it an overture for the most complete treatment given in the following chapters. The elements, themes and motives announced here will be expanded and explored extensively later. I will give a deeper treatment of the stages and difficulties associated with the contemplative journey, along with many suggestions for exercises. When we set off we must remember that although the horizon of contemplative practice is infinite, each and every step we take is already invaluable.

Contemporary Contemplative Research

On August 12, 1904, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote to the young poet Franz Kappus about loneliness:

When talking about loneliness again, it becomes increasingly clear that this is not something that one can accept or reject. We are lonely We can deceive ourselves and act as if this were not so. That's it. But how better it is to realize that we are, yes, even to propose to assume it. [1]

Contemplative practice means, among other things, being practiced alone. This does not mean melancholic or self-indulgent contemplation, but rather to practice a special form of remembrance of the past, awareness of the present, and imagination of the future in a way that is life-giving, clear and intuitive. We learn to be properly lonely, and bring the depth of our loneliness to the world with grace and altruism.

Therefore it is important to reserve moments for reflection, for contemplative exercises, and for meditation. It can be thirty minutes in the morning or in the afternoon or both. No matter the amount of time spent, the fruits of such activity are many and significant. For example, when we practice to find a correct relationship with the problematic thoughts and feelings that occupy our inner life, we learn to form correct mental judgments and habits that benefit us in our daily lives. The angry reaction that would come out

Therefore it is important to reserve moments for reflection, for contemplative exercises, and for meditation. It can be thirty minutes in the morning or in the afternoon or both. No matter the amount of time spent, the fruits of such activity are many and significant. For example, when we practice to find a correct relationship with the problematic thoughts and feelings that occupy our inner life, we learn to form correct mental judgments and habits that benefit us in our daily lives. The angry reaction that would come out

normally from our lips or the violence we can unleash on our momentary adversary is repressed. We have come to know the dynamics of the problem well by having rehearsed it internally, and now the real world version no longer catches us by surprise or with our guard down. We grow to become, as Daniel Goleman calls it, "emotionally intelligent" [2]. I will return to this and other benefits of contemplative practice later, but the important thing here is that long after the practice session is over, its fruits continue to appear.

We don't need, we really shouldn't, try to meditate all the time. The time we reserve for it in the morning or afternoon should have a beginning and an end. The fruits of meditation, however, will bring together all aspects of our lives, benefiting not only us, but also others. Dedicating specific moments to contemplative practice may be the most obvious and often the most difficult part of the job. Inevitably it seems that once the time and place to sit have been found, a forgotten cell phone rings, or the cry of a beloved child goes through the morning air and the closed door. At such moments we feel the truth of the saying that the descent into the stillness of meditation seems to invoke the tumult.

If we are able to overcome such distractions, whether external or internal, the time we spend on a practical session can change everything. Time is important, and our appreciation of that importance can help us create a space for it in our busy lives. Certainly the contemplative practice can invigorate us and help us to calm the tumult of life, but it also offers the occasion for something else. Through meditation I turn to aspects of the world and of myself that I tend to forget otherwise (such as attention distraction, unnecessary irritability, and others), and what I do with a quality of attention that is rare in normal life. We often forget the greatness of the world we inhabit as well as the mystery of our lives. The simple act of stopping to reflect, and of maintaining our consciousness s soft but firm- in these forgotten dimensions of the world and of our lives is a service and even a duty. Do you not stop to attend to the child you love even though you are busy? Can they not stand up to cultivate loneliness, which is the true starting point?

Once recognized, silence can become as important as sound, inaction as essential to us as action. Each element balances and supports its opposite. Once this sacred dimension of our contemplative work has been discovered, its importance increases and we address it more easily. I come to realize that in the end this work is not about me, my improvement or my development. Contemplation is much more objective and its value much more real than I recognized at the beginning. My inner activity while meditating has an intrinsic value. Getting started is important not only for me, but for your own good (qualitative effect).

Contemplative practice within a group, especially with the guidance of a reliable and competent teacher, is often experienced as easier. The presence of others and the efforts they make seem to resonate with our own efforts, improving and compensating for the limited resources. Even so, meditative work is, after all, solitary work. It is our business, and no help can or should free us from it. Collective meditation should be guided by the principle of freedom within the group. As long as our individuality is honored, or, in Rilke's words, as long as our loneliness is respected and protected, then our work in freedom with others can be an important help.

Loneliness is more than a key to contemplative practice. As Rudolf Steiner once said and Rilke emphasized, loneliness is actually the main feature of our modern era, and in the future the trend will increase. [3] Rilke identified the origins of this characteristic with the birth of modern poetry. In his essay L rica Moderna of 1898, with 23 years, Rilke pointed out 1292 as the dawn of modern lyric, the birth of poetry Woe to literature as we know it. The event that Rilke refers to is the publication, by Dante, of his small collection of poems entitled Vita Nuova (New Life) in which he gave the world a description of His unrequited love for Beatrice. For Rilke, Dante's poems and his lonely struggle with love marked the beginning of the central characteristic of human consciousness: loneliness. “From the first attempt of the individual to find himself in the tide of fleeting events, since the first struggle amid the clamor of daily life to hear the deepest loneliness of his own being, there has been the modern lyric” (Rilke) [4 ]

Therefore "in the midst of the clamor of daily life" we are already hermits and will continue to be for a long time. As modern souls we are called to the "deepest loneliness of our own being." Our task, therefore, is not to deny this fact but to accept it and move forward with that sure understanding. Through patient practice we can deepen the stillness that we all carry within. Surprisingly, we will discover through solitude, that a new fullness develops in human relationships, and we will learn to practice a new kind of love that can flourish between solitudes. Instead of isolating ourselves, loneliness will connect us with the depths of others in ways that were

Therefore "in the midst of the clamor of daily life" we are already hermits and will continue to be for a long time. As modern souls we are called to the "deepest loneliness of our own being." Our task, therefore, is not to deny this fact but to accept it and move forward with that sure understanding. Through patient practice we can deepen the stillness that we all carry within. Surprisingly, we will discover through solitude, that a new fullness develops in human relationships, and we will learn to practice a new kind of love that can flourish between solitudes. Instead of isolating ourselves, loneliness will connect us with the depths of others in ways that were

impossible before. [5] The love that the individual treasures - the loneliness of the neighbor - is the principle on which we will build communities based on freedom one day. [6] As we move forward, loneliness and love will be inseparable.

The Cultivation of Virtue

When meditative attention education first made its way in the West from Asia, one of the first groups to take advantage of it was Mossad, the Israeli version of the CIA. The usefulness of samadhi or "one-focus attention" was obvious to them. The objectives to which they were directed were classified. Since then many military organizations, basketball teams, and companies have used contemplative methods to improve their performance and reduce stress. I raise this issue not so much because I want to discuss the suitability of teaching meditation to commands (martial arts have long combined meditation with action) but because I want to point out the disconnect between virtue and contemplative practice. Meditation, even meditative achievement, does not automatically guarantee that the meditator possesses a good moral judgment or practices an ethical life.

The stories in this aspect are innumerable, both ancient and modern. It is said that the wise Indian Milarepa (1052-1135) used his miraculous siddhis or psychic powers to destroy a greedy landowner who treated his relatives in an inhuman way. Anger control problems have obviously been an important issue for a long time, even among teachers. In recent years it seems that almost every spiritual tradition has been plagued by financial or sexual scandals. Skilled and well-meaning teachers are not immune to these temptations. All this points to a fundamental truth, that is, for the meditative practice to have value as a positive contribution to the world, it must rest on the foundations of a separate effort committed to moral development. In the Buddhist tradition this is called sila or "virtue, " and it is claimed to be the cornerstone of the Noble Eightfold Path. Within this tradition the practices of correct discourse, correct action, and earning a living in a correct way are understood as essential for moral development. Those who undertake training within the Buddhist tradition must observe precepts or ethical rules: five for lay practitioners and 227 for a fully ordained monk.

In our time, strict adherence to a set of precepts, no matter how carefully formulated and well intentioned, violates our sense of autonomy. We can value moral orientation, but we ourselves have become the final judges of moral judgment. We possess the ability, if we quiet our passions, to clearly discern the right decision in any situation. When the medieval mystic Marguerite Porete wrote about the virtues, "I move away from you", she was burned at the stake by the "Heresy of the Free Spirit." [7] She was advanced in her time by stating that her love for God would be enough to guide her life. Linking his opinions with his renowned predecessor, he cited the famous phrase of St. Augustine, "Love and do what you want, " but that did not help. The Church could only imagine the chaos that would follow if everyone followed their own sense of good and evil. Although we can sympathize with them, it seems clear that the moral conditions for contemplative practice cannot and do not need to be imposed from the outside, in a sense, all of us are (or should be) "heretics" followers of the free spirit.

In our time, strict adherence to a set of precepts, no matter how carefully formulated and well intentioned, violates our sense of autonomy. We can value moral orientation, but we ourselves have become the final judges of moral judgment. We possess the ability, if we quiet our passions, to clearly discern the right decision in any situation. When the medieval mystic Marguerite Porete wrote about the virtues, "I move away from you", she was burned at the stake by the "Heresy of the Free Spirit." [7] She was advanced in her time by stating that her love for God would be enough to guide her life. Linking his opinions with his renowned predecessor, he cited the famous phrase of St. Augustine, "Love and do what you want, " but that did not help. The Church could only imagine the chaos that would follow if everyone followed their own sense of good and evil. Although we can sympathize with them, it seems clear that the moral conditions for contemplative practice cannot and do not need to be imposed from the outside, in a sense, all of us are (or should be) "heretics" followers of the free spirit.

Instead of rules, the practitioner can cultivate a set of fundamental dispositions or attitudes that lead to virtue. When the practice is based on these dispositions or attitudes one feels that an adequate moral foundation has been established. The first attitude is that of humility . Steiner calls humility the portal or door that the beholder must cross. [8] Through it we put our own interest aside and recognize the great value of our fellow men. Humility leads to the "path of reverence." Here I am not speaking of reverence to a person, but rather of reverence towards the high principles that we seek to embody. The fundamental attitudes of humility and reverence are incompatible with selfishness, which is the source of much moral confusion.

How do we cultivate these attitudes at the beginning of a practical session? Here, as always, the individual must be taken into account. What works for one will hinder another. For medieval mystics, prayer was a safe entrance; These meditators, like many today, used the words of Scripture to cultivate humility and devotion. Other modern contemplatives, however, may find their association with traditional religion so problematic that prayer is simply impossible. Many find the path to humility and reverence more easily through wonder and awe inspired by the splendor of nature. To evoke in the mind the night starry sky or the blue vault of the sky, or perhaps a special favorite refuge, such as a rock, a tree or a river bank, can help us find our way to the portal of humility and The path of reverence.

In many individuals with whom I have worked, I have felt the deep peace and simple joy they experience in finding the place of inner devotion when they spent time practicing prayer or meditation on nature. They often want to stay there and deepen their devotion, cultivate it not as a step on the path towards contemplative research, but as a practice in its own right. As I will discuss this possibility later, for our purposes we will now recognize the power of humility, reverence and devotion, and recognize that these attitudes provide a solid moral foundation for meditation. Its cultivation is a practice in virtue. Every contemplative practical session should begin by crossing the portal of humility and finding the path of reverence.

Inner Wellness

When we retreat for the first time from outside activity and take care of the mind, we are surprised at the mischievous confusion that generally prevails. Thoughts move quickly and without control, as coming from nowhere. Our daily mental planner suddenly appears with three pressing and forgotten commitments that simply must be noted before we forget them. Or our mind is heading towards a recent discussion with our spouse, and what we should have said to defend ourselves, etc. At first the very idea that the mind can be still, clear and under my control seems like a remote possibility if not an impossibility. Long-forgotten or suppressed emotions re-emerge; Thoughts seem to have an unstoppable life, producing new thoughts through a completely own logic. With the mind in this state, little can be expected of meditation. Therefore the initial task is the cultivation of a mental and emotional balance or inner well-being. Think of it as internal hygiene, if you wish. It is an essential and recurring part of the practice, and we should never abandon it.

When we retreat for the first time from outside activity and take care of the mind, we are surprised at the mischievous confusion that generally prevails. Thoughts move quickly and without control, as coming from nowhere. Our daily mental planner suddenly appears with three pressing and forgotten commitments that simply must be noted before we forget them. Or our mind is heading towards a recent discussion with our spouse, and what we should have said to defend ourselves, etc. At first the very idea that the mind can be still, clear and under my control seems like a remote possibility if not an impossibility. Long-forgotten or suppressed emotions re-emerge; Thoughts seem to have an unstoppable life, producing new thoughts through a completely own logic. With the mind in this state, little can be expected of meditation. Therefore the initial task is the cultivation of a mental and emotional balance or inner well-being. Think of it as internal hygiene, if you wish. It is an essential and recurring part of the practice, and we should never abandon it.

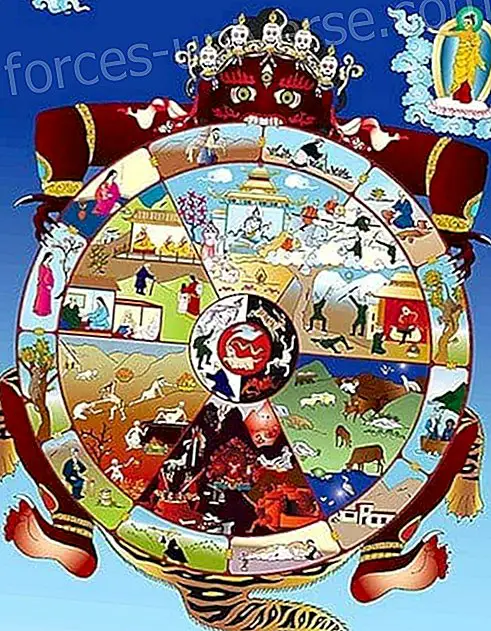

The classification of mental afflictions and negative emotions can be found in Western psychology as well as in Buddhist. Certainly, Buddhism speaks of 84, 000 kinds of negative emotions! Although the 84, 000 are reduced to five fundamental problems: hate, desire, confusion, pride and envy. [9] Another useful way of organizing alterations is based on a triformed image of human inner life: thought, feeling and will. Each of these areas can show pathological tendencies, which can be noticed by the meditator and for which contemplative exercises can be provided. The first order of the matter, therefore, concerns the practice designed to mitigate such alterations. While there are many exercises of that style, several of which I will give in Chapter 3, the exercise I give here is based on an exercise suggested by Rudolf Steiner and refers to the care of our emotional life. [10]

Normally we see experiences, emotions and thoughts from the inside. We identify with them. They are us, we are them. In this sense we are entangled in our emotions and thoughts, and we experience a sense of personal identity through them. Such an experience of the self is an illusion and a source of problems. The first exercise, therefore, has been selected to provide us with some distancing from our own experiences, allowing us to consider them from the outside and work with them from a new point of view. The discovery of this new and high point of view is not always easy, but once we learn the way to it, then the narrow path to emotional equanimity can open us up and allow us to consider the m It is intense emotional struggles of daily life from the point of view with which we have become familiar thanks to meditation. By way of introduction, I will report an episode of the life of the American civil rights leader, Dr. Martin Luther King.

During his years of work in defense of American blacks, Martin Luther King incessantly advocated non-violent action as a means of drawing attention to the oppression of blacks, especially in the South (of the United States). He received many threats and suffered several attempts on his life. On one occasion his home in Montgomery, Alabama, was blown up while he was in a church meeting. [11] The porch and the front of the house were badly damaged. His wife, Coretta, and daughter Yoki were at the back of the house at the time, and no one was injured. When Mr. King arrived, an agitated crowd of hundreds of black neighbors had gathered, ready to retaliate against the policemen there. His beloved leader and his family had been attacked. Faced with the imminent possibility of a street riot, police asked King to address the crowd. King came out to what was left of his front porch, raised his hands and everyone was silent. He said:

We believe in law and order. Do not do anything rash. Do not bear your weapons. Who to iron kills iron dies. Remember that this is what God said. We do not advocate violence. We want to love our enemies. I want you to love your enemies. Be good to them. Love them and let them know that you love them. I did not start this boycott. You asked me to serve as a spokesperson. I want it to be known throughout this country that if this movement ends with me, this movement will not end. If it ends with me our work will not stop. Well, what we are doing is correct. What we are doing is fair. And God is with us.

When Martin finished, everyone went home without violence, saying "Amen" and "God bless you." There were tears on many faces. Surely King had felt the same emotions of anger at the attempt on his life and the lives of his relatives, but he was also able to find a place in himself from which he could speak and act, from which he did not respond to hate with hate, but faced hate with love.

In our own lives we experience similar insurances although surely minor ones, but they can lead us to long periods of disturbing anger and internal turmoil. The contemplative exercise begins by selecting from our past experiences an occasion of hatred, envy, desire, anger, etc. It should be strong but not overwhelming or too recent. Then, having found our way to the portal of humility and the path of reverence, we relive the selected occasion. As you evoke the situation again in the mind, it is important to allow the associated negative emotions (desire, pride, anger ...) to arise once again. Feel their strength, feel the agitation of feelings and the emotional hangover that, if left free, could lead you back to the dark and uncontrolled emotions of the original situation. Only by giving up the reins a little to these feelings can we practice their overcoming and learn to control the situation in a new light. When emotions begin to take control, such as the arrival of the furious neighbors of Martin Luther King, seek within you a higher ground, look for a place from which you look inside yourself and the whole situation. Cover the conflicting parts of the drama with your field of attention. Feel the contention between two selves. Get away from the hangover of destructive emotions and take your place as witnesses. Find your way from the mentality of the crowd to the Martin Luther King inside. From your new point of observation, proceed to experience the inner dynamics that are at stake in the situation.

In our own lives we experience similar insurances although surely minor ones, but they can lead us to long periods of disturbing anger and internal turmoil. The contemplative exercise begins by selecting from our past experiences an occasion of hatred, envy, desire, anger, etc. It should be strong but not overwhelming or too recent. Then, having found our way to the portal of humility and the path of reverence, we relive the selected occasion. As you evoke the situation again in the mind, it is important to allow the associated negative emotions (desire, pride, anger ...) to arise once again. Feel their strength, feel the agitation of feelings and the emotional hangover that, if left free, could lead you back to the dark and uncontrolled emotions of the original situation. Only by giving up the reins a little to these feelings can we practice their overcoming and learn to control the situation in a new light. When emotions begin to take control, such as the arrival of the furious neighbors of Martin Luther King, seek within you a higher ground, look for a place from which you look inside yourself and the whole situation. Cover the conflicting parts of the drama with your field of attention. Feel the contention between two selves. Get away from the hangover of destructive emotions and take your place as witnesses. Find your way from the mentality of the crowd to the Martin Luther King inside. From your new point of observation, proceed to experience the inner dynamics that are at stake in the situation.

Falling under the domain of negative emotions is like going blind. When we get carried away by anger, desire or envy, we don't really see who or what is before us. We cannot judge the forces at play or intuit the right path. Now, from the new point of observation, try to see who is really before you and what forces are really active. In the middle of the event, feel the story behind it and the possibility that exists beyond it. The events of the day and certainly your entire life have led you to encounter and negative emotions. They are factors that can be seen and appreciated.

If there are other people involved, imagine them in a similar way. They also bring a story and a future to the encounter; they also experienced events unknown to you during the day. Do not psychoanalyze yourself or other people. Rather, simply appreciate, sympathetically and objectively, the complexity and multiple dimensions of the drama that is being developed. It is not about finding the right or wrong but compassionate understanding. The emotional force of the exchange, although still present, is now seen and experienced differently. When we speak and act from this place of compassionate understanding, we are better able to disperse the attack of anger, and respond to hate with love.

If we are sailing in the open sea and a storm hits us, how do we respond? Simply cursing the wind and the blows of the waves would be immature as well as ineffective. It is much better to accept the fact of the storm, over which we have no control, and turn our attention to what we do have control over, that is, ourselves and the ship. How much sail should we have hoisted, what should be the course, is the cargo tied and the hatches closed? Life presents us with storms and tests. We often have no responsibility for its creation, but we do have responsibility for how we deal with them. This exercise, therefore, is not designed to empty us of emotions but to guide us through the seas.

It should be clear that we do not cultivate equanimity to be better prepared for a counterattack, but to be able to find an opportunity for understanding and reconciliation. From the observation point of the helm or the high ground we could discover the insignificant basis for our envy or the illusory motives of our desires. The knowledge thus obtained does not automatically lead to the destruction of envy or desire. It is much harder to live our knowledge than to have them! However, a good start is not to give ourselves to our emotions, but to stop to put aside the ego, seek a higher ground, discover the Martin Luther King in us, and thus maintain the conflict with a much more generous pair of hands. . Sometimes I call this the Martin Luther King exercise because King, although he had human weaknesses, often seemed to live, speak and act from a high place beyond the ego, a place we can call "the silent self."

The Birth of the Silent Self

In an essay for a student newspaper, Thomas Merton wrote about the importance of creative silence, in which one addresses from what he called the "social self, " which is defined by our multiple interactions with others, toward an "I deeper silent ”[12], the quiet captain of the ship or the observer from“ the hill ”. King had found countless times the way to that silent, deeper self, and so he could speak and act from him instead of succumbing to the group mentality. To wake up, as Thoureau urges us to do, we need to give birth to the silent self in the midst of our conventional life of duties and desires. The cultivation of deep inner well-being can culminate in the birth of the silent self that is usually obscured and forgotten.

The poet Juan Ramón Jiménez captures the mystery of our deepest identity - our silent self - in his poem "I am not me"

I'm not me.

I am this

That goes by my side without me seeing it;

That, sometimes, I will see,

And that, sometimes, I forget.

He who is silent, serene, when I speak,

He who forgives, sweet, when I hate,

He who walks where I am not,

The one that will remain standing when I die. [13]

Jiménez treats here the great mystery of our true identity. You cannot unravel in a few lines, but the experience is unmistakable. Having crossed the portal of humility and having found the path of reverence, the gradual calm of the mind, together with the improvement of attention, silence the social self. In the contemplative space that then opens in us, the common self vanishes and we begin to operate with what Jimnez calls the non-self. Typically unnoticed, only he endures, only he will remain standing when I die. That is to say, all the external aspects of my person (gender, profession, factual knowledge ) will pass, and only the non-I will endure. In Buddhism this is the turn towards an-atman or Non-Yo; in Christianity it is the discovery of Not me, but Christ in m of St. Paul. It is as if we shifted our mode of consciousness from the center to the periphery, and in doing so we experienced everything again. [14] An event that aroused anger, or an encounter that stimulated desire, changes with the birth of the non-self. Anger may be justified, and we can even value the feeling of moral outrage before turning to the non-self. Although once we give birth to the non-self, we deal with our anger or our sorrows in a different way, as King dealt with the angry crowd.

Rumi began his life not as a poet and as a poet, but as a sage of literature and Islamic philosophy. His encounter with the mystic Shams-i-Tabriz at 37 years of age began the profound transformation, but it took the tragic death of Shams three years later., and the uncontrollable duel that followed, to open wide the gates of poetry, music and spiritual communion. Rumi needed many months to go from the self that only saw the loss, to the non-self or silent self that could rediscover an inner relationship with Shams even after of his death. By reading Rumi's poem The Guest House, it reminds us of the depth of his suffering and his grief. [15]

This being a human being is like managing a guest house.

Every day a new visit.

A joy, a sadness, a disappointment,

some momentary awareness comes

As an unexpected visitor.

Welcome them and add them all,

even if they are a group of sentences,

that violently undervalue

the furniture of your house.

Treat each guest honorably because

could be making space

For a new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the evil,

receive them at your door smiling

and invite them in.

Be grateful to everyone who comes

because all have been sent

as guides from beyond

Todo lo que tenemos de Rumi, su poesía y su danza derviche, surgió con el nacimiento de su yo silencioso, o con el nacimiento de un yo superior que no tiene nada en común con el yo social convencional. Incluso aprendió a dar la bienvenida y tratar honorablemente la pérdida de su querido Shams. Seguramente, su encuentro con Shams –su verdadero amigo espiritual- fue “enviado como un guía del más allá”, pero también lo fue su pérdida. A partir de esa pérdida surgieron las miles de líneas que conforman su extraordinaria obra poética, el Mathnawi, conocido durante siglos como “el Qur'an in Pahlavi”.

Según mi experiencia, si hemos practicado el ejercicio Martin Luther King en la quietud de la contemplación, entonces cuando nos encontremos una situación comparable en la vida real tendremos a nuestra disposición un nuevo recurso. Aún nos enfrentaremos a nuestra némesis, tendremos esa terrible y temible confrontación, pero ahora cuando nuestras emociones surgen y la resaca empieza a arrastrarnos, nos dirigimos automáticamente a un terreno más elevado. Buscamos y encontramos el estrecho sendero que nos conduce hasta el yo silencioso, un sendero que a menudo no encontrábamos en el pasado. Cuando el violento ataque nos golpea caminamos por un sendero que hemos limpiado de emociones destructivas y ahora tiene generosidad. Como consecuencia, nuestras palabras y acciones tienen un origen distinto, un origen que busca la comprensión mutua y la reconciliación en vez de la victoria. También podemos encontrarnos que esta forma de ser en ese momento produce una respuesta similar en la persona que tenemos delante. La gente con que nos topamos puede encontrarse hablando con una generosidad poco frecuente. A veces sucede que, en lugar de violencia, puede surgir un respeto por el otro, y con ello surge un nuevo comienzo para una relación.

Según mi experiencia, si hemos practicado el ejercicio Martin Luther King en la quietud de la contemplación, entonces cuando nos encontremos una situación comparable en la vida real tendremos a nuestra disposición un nuevo recurso. Aún nos enfrentaremos a nuestra némesis, tendremos esa terrible y temible confrontación, pero ahora cuando nuestras emociones surgen y la resaca empieza a arrastrarnos, nos dirigimos automáticamente a un terreno más elevado. Buscamos y encontramos el estrecho sendero que nos conduce hasta el yo silencioso, un sendero que a menudo no encontrábamos en el pasado. Cuando el violento ataque nos golpea caminamos por un sendero que hemos limpiado de emociones destructivas y ahora tiene generosidad. Como consecuencia, nuestras palabras y acciones tienen un origen distinto, un origen que busca la comprensión mutua y la reconciliación en vez de la victoria. También podemos encontrarnos que esta forma de ser en ese momento produce una respuesta similar en la persona que tenemos delante. La gente con que nos topamos puede encontrarse hablando con una generosidad poco frecuente. A veces sucede que, en lugar de violencia, puede surgir un respeto por el otro, y con ello surge un nuevo comienzo para una relación.

Esta práctica habla sólo de un aspecto problemático de la vida interior, pero puede resultar de enorme ayuda si se asume y se practica sistemáticamente. Describiré otras prácticas para el bienestar interior en el capítulo 3. A través de ellas no buscamos en último término un mero control de nuestras emociones sino transformarnos hasta tal punto que seamos generosos y compasivos por naturaleza en la vida. En vez de controlar nuestras emociones, hemos de llegar a ser personas diferentes, en las que estas características positivas sean intrínsecas. Tales cambios no suceden con rapidez. Somos un medio extraordinariamente resistente al cambio. Utilizando la metáfora de una escultura, nosotros seríamos al mismo tiempo la testaruda piedra, el cincel transformador y las manos del artista. El físico Erwin Schrödinger escribió:[16]

Y así en cada paso, en cada día de nuestras vidas, como si dijéramos, algo que hasta entonces ya poseíamos y que tenía una determinada forma, ha de cambiar, ser superado, ser eliminado y reemplazado por algo nuevo. La resistencia de nuestra primitiva voluntad está correlacionada físicamente con la resistencia de la forma existente al cincel transformador. Pues nosotros mismos somos el cincel y la estatua, conquistadores y conquistados al mismo tiempo, es una verdadera y continua “auto-conquista” (Selbstüberwindung)

Si recorremos, aunque solo sea una parte, del sendero hacia la meta de la auto-transformación, entonces el mundo a nuestro alrededor cambia también. Se ve con deleite y con un corazón firme y abierto. Nos sentimos como nutridos por una corriente oculta; tenemos paciencia y manifestamos buen juicio. El primer Salmo podría haberse escrito teniendo en cuenta esto:[17]

Dichoso el hombre

que no sigue el consejo del impío,

ni en el camino del errado se detiene,

ni en la reunión de los malvados toma asiento,

sino que en la ley divina se complace

y sobre ella medita, día y noche.

Es como el árbol plantado en los arroyos,

que da el fruto a su tiempo

y sus hojas no se secan,

en todo lo que hace tiene éxito

Meditación e Investigación Contemplativa

El ejercicio Martin Luther King se ocupaba del establecimiento de una vida interior estable y saludable, y con el nacimiento del yo silencioso o no-yo. Si falta este cimiento entonces todo trabajo ulterior será en vano, conduciendo sólo a engaños y proyecciones. Por esta razón, la preparación es esencial para toda la práctica contemplativa subsiguiente. Porque la práctica contemplativa no se ocupa exclusivamente, ni siquiera fundamentalmente de nuestros problemas, falta de atención y aflicciones, por muy importantes que puedan resultar para nosotros

El ejercicio Martin Luther King se ocupaba del establecimiento de una vida interior estable y saludable, y con el nacimiento del yo silencioso o no-yo. Si falta este cimiento entonces todo trabajo ulterior será en vano, conduciendo sólo a engaños y proyecciones. Por esta razón, la preparación es esencial para toda la práctica contemplativa subsiguiente. Porque la práctica contemplativa no se ocupa exclusivamente, ni siquiera fundamentalmente de nuestros problemas, falta de atención y aflicciones, por muy importantes que puedan resultar para nosotros

personalmente. En el centro de la práctica está la meditación adecuada, que se ocupa de aquello que tiene valor para todos los seres humanos. Quizás mejor dicho, se ocupa de la verdadera naturaleza de las cosas.

Nosotros comprendemos que las leyes de la geometría de Euclides no dependen ni de mí ni de mis preferencias. Asimismo, los descubrimientos de la ciencia son verdaderos en todos los países y en todos los tiempos, de otro modo los medicamentos antivirales y los teléfonos móviles no funcionarían en África como funcionan en América. El mundo no está organizado alrededor de mí, sino que tiene entidad propia. Cuando profundizamos en los ejercicios diseñados para promover la higiene interior, meditamos sobre la forma de ser de las cosas. Buscamos aquello que trasciende nuestros problemas personales. Esto no implica que nos desinteresemos de la condición humana, sino que dejamos a un lado los problemas particulares que afrontamos. Buscamos, a través de la meditación, confrontarnos con lo profundo y lo elevado, las realidades espirituales y morales que subyacen a todas las cosas.

Yo veo esto como una progresión. Habiendo entrado a través del portal de la humildad, habiendo encontrado el sendero de la reverencia, habiendo cultivado una higiene interior, y habiendo dado nacimiento al yo silencioso, emprendemos la meditación correcta. En la meditación nos movemos a través de una secuencia de prácticas que comienza con la simple captación contemplativa y después profundiza esa captación hasta la investigación contemplativa sostenida, que con buena voluntad puede conducir al conocimiento contemplativo.

Aunque requiere objetividad igual que la ciencia convencional, la investigación contemplativa difiere de la ciencia en un aspecto muy importante. Donde la ciencia convencional se esfuerza por desvincularse o distanciarse de la experiencia directa por el bien de la objetividad, la investigación contemplativa hace exactamente lo contrario. Busca el compromiso con la experiencia directa, una participación mayor y más plena en los fenómenos de la consciencia. Logra la “objetividad” de una manera distinta, esto es, a través del auto-conocimiento y lo que Goethe denominó en sus escritos científicos un “delicado empirismo”[18]

Después de trabajar higiénicamente sobre sus distracciones mentales y la inestabilidad emocional, el practicante aleja su atención del yo y la dirige a un conjunto de pensamientos y experiencias que van más allá de la vida personal. Las formas y contenidos posibles de la meditación en esta etapa son infinitamente variados. Las meditaciones pueden basarse en palabras, en imágenes, en captaciones de los sentidos, etcétera. Cada uno de estos aspectos tiene algo especial que ofrecernos, y cada uno de ellos será descrito en el capítulo 4. Escogiendo una sencilla flor de este hermoso ramo, podemos dirigirnos hacia la excepcional literatura espiritual de todos los tiempos, oa los poetas y sabios que han dado expresión a pensamientos y experiencias que tienen valor universal. Encontramos en ellos multitud de recursos para la meditación. Por ejemplo un pasaje de la Biblia o del Bhagavad Gita, o una línea de un poema de Emily Dickinson, puede utilizarse como tema de meditación.

Tomad por ejemplo las palabras atribuidas a Tales y que se dice que se inscribieron en el muro del Templo de Delfos: “¡Hombre, conócete a ti mismo!” Al principio este mandato parece sumergirnos de nuevo en nosotros mismos, pero este no es necesariamente el caso. Podemos acoger estas palabras de forma que se dirijan a la condición humana en general y no a nosotros en particular. Al comenzar la meditación, podemos simplemente pronunciar las palabras, repitiéndolas una y otra vez. Entonces podemos profundizar para “vivenciar las palabras”, manteniendo cada una de ellas en el centro de nuestra atención. Con cada palabra o frase hay una imagen o concepto asociado. Nos abrimos camino hacia delante y atrás repetidamente entre la palabra, la imagen y el concepto. Las palabras conocer y ti mismo, por ejemplo, asumen un car cter multifac tico, con muchas capas, incluso infinito. El verso ol nea meditativa es como una estrella en el horizonte, infinitamente lejana pero proporciona orientaci ne inspiraci n.

A causa de su riqueza existen innumerables formas de trabajar con cada meditaci n. Por ejemplo, primero pronuncio lentamente la frase varias veces de manera interior, pronunci ndola silenciosamente para m mismo. Le dedico a cada palabra toda mi atenci n, sintiendo su significado particular. Una vez que he centrado mi atenci n en estas palabras, Hombre, con cete a ti mismo!, desplazo entonces la voz que habla, de tal forma que las palabras sean pronunciadas desde fuera de la periferia, como si provinieran de los lejanos confines del espacio o de las atalayas, del cielo, y de la tierra. Las palabras se me dirigen; son una llamada desde el entorno m s amplio que me rodea. La llamada se dirige espec ficamente am como ser humano. Es una llamada al auto-conocimiento. Escucho la llamada, hago una pausa, y asumo el mandato.

A causa de su riqueza existen innumerables formas de trabajar con cada meditaci n. Por ejemplo, primero pronuncio lentamente la frase varias veces de manera interior, pronunci ndola silenciosamente para m mismo. Le dedico a cada palabra toda mi atenci n, sintiendo su significado particular. Una vez que he centrado mi atenci n en estas palabras, Hombre, con cete a ti mismo!, desplazo entonces la voz que habla, de tal forma que las palabras sean pronunciadas desde fuera de la periferia, como si provinieran de los lejanos confines del espacio o de las atalayas, del cielo, y de la tierra. Las palabras se me dirigen; son una llamada desde el entorno m s amplio que me rodea. La llamada se dirige espec ficamente am como ser humano. Es una llamada al auto-conocimiento. Escucho la llamada, hago una pausa, y asumo el mandato.

Me dirijo primero hacia m mismo como ser humano f sico. Siento el aspecto terrenal, substancial de mi ser: mi cuerpo f sico. Comienzo con mis extremidades, mis manos y brazos, mis pies y piernas. Puedo incluso moverlas ligeramente para sentir su presencia f sica con mayor plenitud. Entonces me centro en mi secci n media, mi pecho y mi espalda. Siento mi respiraci ny mi latido. Estos tambi n forman parte de mi naturaleza f sica. Finalmente me centro en mi cabeza, que descansa tranquilamente en lo alto de mi cuerpo; su s lida forma redonda alberga los sentidos, cerrados ahora al mundo. Las extremidades, el torso y la cabeza forman el ser humano f sico. Me imagino cada uno de ellos y su relaci n mutua. Conozco al ser humano f sico. Descanso durante un tiempo con esta imagen y experiencia en mi interior.

Despu s me dirijo a la vida interior de pensamientos, sentimientos e intenciones. Siento c mo mi voluntad se deja llevar misteriosamente. Mis intenciones para pensar o actuar culminan, a trav s de formas que me son desconocidas, en un flujo coordinado de movimiento. Vivo en esa actividad, que puedo dirigir. Es parte de mi naturaleza. Adem s tengo una vida plena de sentimientos. Los sentimientos de simpat ao antipat a, de agotamiento o alerta, de excitaci no remordimiento est n presentes en mi interior. Siento la importancia que tienen para m, cu nto en mi vida est determinado por ellos o se refleja en ellos. Normalmente s lo soy parcialmente consciente de su importancia ys lo los controlo parcialmente. Su dominio se halla parcialmente velado aunque abierto a mi inter sy respondiendo a mi actividad. Estos sentimientos constituyen una parte de mi naturaleza en no menor medida que mi cuerpo f sico. Finalmente me dirijo a mis pensamientos. Mi vida de pensamiento es a la vez mi vida y adem s participa en algo que me trasciende. Me puedo comunicar con otras personas, compartir mis pensamientos con ellas. Esto indica algo universal en el pensamiento: como todos los demás, participo en una corriente universal de actividad pensadora. Sé, gracias a haberlo vivenciado interiormente, que el pensamiento es parte de mi naturaleza.

Los tres –pensamiento, sentimiento y voluntad- se entrelazan para formar un solo yo. Todos y cada uno de los pensamientos de mi meditación (a menos que me haya distraído) han sido premeditados, intencionados, y siento el flujo y el reflujo de sentimientos asociados con cada pensamiento. De estos pensamientos bien pueden resultar acciones. Los tres forman una unidad natural. Son como las extremidades, el tronco y la cabeza: separables aunque en realidad se encuentran entrelazados. Los tres son necesarios. Los tres son yo. Tranquilamente vivo en los tres y en el uno.

Finalmente, dirijo mi atención lejos del cuerpo, incluso lejos de mis pensamientos, sentimientos e intenciones. Dirijo mi atención a una presencia o actividad que anima pero trasciende todo esto. Se enciende en el pensamiento pero no es el contenido de pensamiento que vivencio. Este tercer aspecto de mí mismo es el más esquivo e invisible, y aun así siento que es el aspecto esencial y universal que es verdaderamente yo y no sólo yo. Sólo lo siento en su reflejo. Podría considerarse mi Yo, pero en una forma que no tiene género ni edad ni posee ninguna característica particular. Sin él sólo sería cuerpo y mente, materia física, sentimientos, pensamientos y hábitos, pero faltarían mi originalidad y mi genio. En el lenguaje de las reflexiones matutinas de Thoureau, estaría condenado a dormir para siempre, porque sólo este ser tiene la posibilidad de despertarme a una vida poética y divina. Al dirigir mi atención hacia este yo silencioso siento los indicios de un Yo que es un no-yo. Lo reconozco también como parte de mí, o quizás yo soy parte de él.

Entonces reúno los tres aspectos –cuerpo, alma y espíritu- en el espacio de mi meditación. Todos ellos conforman el yo; cada uno es real y está presente. Siento su presencia, su realidad, por separado y juntos. Mantengo este sentimiento el mayor tiempo posible, y entonces con una clara intención, vacío mi consciencia de estas imágenes e ideas. Me vacío completamente, pero mantengo mi atención abierta y viva silenciosamente en el espacio meditativo así preparado. He dado forma al vacío con mi actividad. Ahora que el espacio de mi meditación está vacío de mi contenido, de mis pensamientos y sentimientos, puedo mantener una atención abierta sin expectativas y sin tratar de captar nada. Sin tratar de ver o escuchar, sin embargo, puedo sentir o vivenciar algo reverberando en ese espacio, haciéndose sentir durante un tiempo más o menos largo, cambiando y después desapareciendo. Esperando, sin tratar de captar nada, uno se siente agradecido. En las palabras del Tao Te Ching, [19]

Entonces reúno los tres aspectos –cuerpo, alma y espíritu- en el espacio de mi meditación. Todos ellos conforman el yo; cada uno es real y está presente. Siento su presencia, su realidad, por separado y juntos. Mantengo este sentimiento el mayor tiempo posible, y entonces con una clara intención, vacío mi consciencia de estas imágenes e ideas. Me vacío completamente, pero mantengo mi atención abierta y viva silenciosamente en el espacio meditativo así preparado. He dado forma al vacío con mi actividad. Ahora que el espacio de mi meditación está vacío de mi contenido, de mis pensamientos y sentimientos, puedo mantener una atención abierta sin expectativas y sin tratar de captar nada. Sin tratar de ver o escuchar, sin embargo, puedo sentir o vivenciar algo reverberando en ese espacio, haciéndose sentir durante un tiempo más o menos largo, cambiando y después desapareciendo. Esperando, sin tratar de captar nada, uno se siente agradecido. En las palabras del Tao Te Ching, [19]

¿Tienes la paciencia de esperar

hasta que tu lodo se deposite en el fondo

y el agua sea clara?

¿Puedes permanecer inmóvil

hasta que la acción correcta

surja por sí misma?

El Maestro no busca el éxito.

No busca, no espera.

Él está presente y puede dar la bienvenida a todo.

He aprendido a dar la bienvenida a todas las cosas. Una profunda paz se establece en el cuerpo y en la mente. Descanso dentro de esa paz con gratitud. Sintiendo que la meditación está completa, regreso.

En la meditación nos movemos entre la atención enfocada y la atención abierta. Entregamos nuestra plena atención a las palabras individuales del texto que hemos elegido, ya sus imágenes y significados asociados. Entonces avanzamos hacia la relación que mantienen entre ellos de tal forma que se vivencia un organismo vivo de pensamiento. Dejamos que esta experiencia se intensifique al mantener el conjunto de pensamientos interiormente ante nosotros. Puede que necesitemos volver a pronunciar las palabras, elaborar las imágenes, reconstruir los significados, y sentir de nuevo su interrelación para encontrar apoyo e intensificar la experiencia. Después de un período de vívida concentración sobre el contenido de la meditación, liberamos el contenido. Aquello que sujetábamos se ha ido. Nuestra atención se abre. Estamos completamente presentes. Se ha preparado intencionadamente un espacio psíquico interior, y permanecemos en ese espacio. Esperamos, sin expectativas, sin esperanza, tan sólo presentes para recibir lo que pueda o no surgir dentro de la quietud infinita. Si una tímida, naciente experiencia emerge en el espacio que hemos preparado, entonces la recibimos con gratitud y con delicadeza: sin ansia, sin buscarla.

Veo esto como una especie de “respiración” de la atención. Primero permanecemos enfocados atentamente sobre un objeto de contemplación, pero después el objeto es liberado y mantenemos nuestra consciencia abierta, sin enfocar. Estamos respirando, no aire, sino la luz interior de la mente, lo que yo llamo respiración cognitiva . En ella vivimos en un tempo lento, alternando entre la atención enfocada y la apertura. Cuando respiramos la luz de la atención, sentimos un cambio en nuestro estado de consciencia durante la meditación. Se pueden presentar sentimientos de expansión y de unión, de vitalidad y movimiento. Tales sentimientos pueden hacerse especialmente evidentes durante la fase de atención abierta.

Mientras caminaba a través del Boston Common en un estado de reflexión, Ralph Waldo Emmerson describió su experiencia interior en vívidos términos: “ mi cabeza bañada por el despreocupado aire y elevada al espacio infinito, todo mezquino egoísmo se desvanece. Me convierto en un ojo transparente; no soy nada; lo veo todo; las corrientes del Ser Universal circulan a través de mí”.[20] En este famoso pasaje Emmerson escribe acerca de la participación en una realidad más abarcante que él mismo, que llega más allá del pequeño ego de la consciencia convencional. Su yo social, su persona, se ha desvanecido y las corrientes del Ser Universal circulan a través de él. La experiencia de Emmerson sitúa ante nosotros el complejo asunto de la experiencia contemplativa.

El Viaje de Regreso

El viaje de regreso es tan importante como el viaje de ida. Habiendo vivenciado nuestra salida a través de las palabras “¡Hombre, conócete a ti mismo!”, podemos pronunciarlas una vez más interiormente cuando estamos regresando. Cuando escuchamos por primera vez estas cinco palabras, su plenitud aún no era evidente, pero ahora que las hemos meditado, una profundidad o aura de significado las impregna. En el viaje de regreso escuchamos las palabras de una manera diferente; portan consigo capas de vivencias e imágenes. Buscamos integrar esa riqueza de experiencias en nuestras vidas según regresamos a casa.

El viaje de regreso es tan importante como el viaje de ida. Habiendo vivenciado nuestra salida a través de las palabras “¡Hombre, conócete a ti mismo!”, podemos pronunciarlas una vez más interiormente cuando estamos regresando. Cuando escuchamos por primera vez estas cinco palabras, su plenitud aún no era evidente, pero ahora que las hemos meditado, una profundidad o aura de significado las impregna. En el viaje de regreso escuchamos las palabras de una manera diferente; portan consigo capas de vivencias e imágenes. Buscamos integrar esa riqueza de experiencias en nuestras vidas según regresamos a casa.

Hemos nacido en una vida de servicio y trabajo. This is important. La meditación no es ninguna evasión. Sólo es una preparación para la vida. Regresamos a nosotros mismos con mayor profundidad, más despiertos, y reafirmados por nuestro contacto con lo infinito, con los misterios de nuestra propia naturaleza, con lo divino. Si nuestra meditación ha tenido éxito, podemos incluso ser reticentes a regresar. Tal reticencia, sin embargo, no se halla en consonancia con los fundamentos morales del amor y el altruismo que establecimos al comienzo. Los frutos de la vida meditativa no son para que los acaparemos, sino para compartirlos. La contemplación se emprende adecuadamente como un acto desinteresado de servicio, y así el regreso es la verdadera meta. Si hemos vivido rectamente en el sagrado espacio de la meditación entonces seremos más aptos, más intuitivos para la vida y la amaremos aún más.

Si entramos a través del portal de la humildad, entonces salimos a través del portal de la gratitud. Hay un número infinito de maneras de decir gracias. De ese modo también existen incontables formas de cerrar una sesión meditativa. En la tradición Budista uno sella la meditación al dedicar sus frutos al beneficio de todos los seres que sienten, para que puedan liberarse del sufrimiento. En otras tradiciones uno cierra con una plegaria de gratitud, como el Salmo 131:[21]

Mi corazón, Señor, no es altanero,

ni mis ojos altivos.

No voy tras lo grandioso,

ni tras lo prodigioso, que me excede,

mas allano y aquieto mis deseos,

como el ni o en el regazo de su madre:

como el ni o en el regazo,

as est n conmigo mis deseos.

La Experiencia Contemplativa

Con la pr ctica contemplativa aparece la experiencia contemplativa, esta puede ser del tipo experimentado por Emmerson o puede tener mir adas de otras variantes. Qu hemos de hacer con tales experiencias?

Con la pr ctica contemplativa aparece la experiencia contemplativa, esta puede ser del tipo experimentado por Emmerson o puede tener mir adas de otras variantes. Qu hemos de hacer con tales experiencias?

Las tradiciones contemplativas asumen un amplio conjunto de puntos de vista en relaci n con el significado de las experiencias vividas durante la meditaci n. Cu l es la actitud adecuada del meditador hacia tales experiencias? En un extremo tenemos las palabras del siglo XVI de San Juan de la Cruz, que fue un profundo meditador. Despu s de relatar con extraordinaria precisi n una lista de experiencias contemplativas, recomienda que nos alejemos de todas esas distracciones, que nos desv an de la tarea principal, tal como l la ve a, el establecimiento de la fe.

Debemos desencumbrar el intelecto de estas captaciones espirituales gui ndolo y dirigi ndolo a trav s de ellas hasta la noche espiritual de la fe. Una persona no debiera guardar o atesorar las formas de estas visiones impresas en l, ni debiera tener el deseo de aferrarse a ellas. Al hacerlo, lo que habita en su interior le entorpecer a (aquellas formas, im genes, y figuras de personas), y no viajar a hasta Dios a trav s de la negaci n de todas las cosas Cuanto m s desea uno la oscuridad y la aniquilaci n de s mismo en relaci n con todas las visiones, exterior o interiormente perceptibles, mayor ser la infusi n de fe y consecuentemente de amor y esperanza, ya que estas virtudes teol gicas aumentan unidas.[22]

San Juan de la Cruz por tanto aboga por que abracemos la profunda y oscura noche de la fe.

Por otra parte, las tradiciones Gnósticas y místicas de todos los pueblos han atesorado la iluminación de la consciencia por medio de la meditación y los conocimientos que se derivan de la experiencia contemplativa. Se pueden hallar textos relativos a estas experiencias en cada cultura indígena y en toda tradición de fe. El psicólogo de Harvard, William James buscó a aquellos que habían tenido sólidas experiencias místicas, y escribió sobre la importancia de una ciencia de esas experiencias. La detallada presentación de Rudolf Steiner de sus propias experiencias, constituye un extraordinario ejemplo de meditador moderno, científicamente orientado y filosóficamente entrenado, que escribe y habla directamente a partir de su experiencia meditativa. Me sitúo dentro de este linaje contemplativo y creo que puede derivarse mucho provecho del trabajo contemplativo continuado. El valor potencial de las experiencias contemplativas –no sólo para el meditante, sino también para la sociedad- requiere que nos tomemos estas experiencias meditativas con gran seriedad.

Para que la investigación contemplativa ocupe su lugar entre los caminos más apreciados por la humanidad para llegar hasta el conocimiento verdadero, muchas personas deben asumir sus métodos, aplicarlos con cuidado y consistencia, y comunicarse sus experiencias entre ellas hasta alcanzar un consenso. Las etapas de la investigación contemplativa incluyen todas aquellas que he descrito desde el fundamento moral de la humildad y la reverencia, pasando a través de la higiene, hasta la meditación sobre un determinado contenido. Ese contenido puede ser un tema de investigación o una pregunta. Describiré con mucha más profusión en capítulos posteriores el ámbito y prácticas de la investigación contemplativa tal como yo la veo, pero resumiendo, sería aplicar la respiración de la atención a la investigación que uno lleva a cabo. Creo que de una manera informal e inconsciente ya es parte del proceso de descubrimiento de los individuos creativos.

Mientras San Juan y los Budistas tienen razón al alertarnos en relación con los peligros de apego a los estados alterados de consciencia oa las extraordinarias experiencias, podemos cultivar una orientación saludable, desapegada. El problema potencial es nuestra actitud, y no las experiencias en sí. Es por tanto de suma importancia crear una relación correcta con la experiencia contemplativa, para que no se convierta en una distracción de la meta principal. En particular, uno debería abstenerse de explotar las experiencias o incluso de interpretarlas prematuramente. La actitud más saludable es la de la simple aceptación, tratando tales experiencias como fenómenos inesperados cuyo significado se nos revelará en su momento, pero que no necesitan ser comprendidas inmediatamente. Las experiencias vivenciadas durante la meditación pueden ser novedosas y maravillosas, y podemos observarlas apreciativamente, pero deberíamos abstenernos de hablar de ellas excepto con un profesor, colega o amigo de confianza. En las etapas más avanzadas de la práctica meditativa, el significado se une a la experiencia, pero al principio usualmente no. Con esto quiero decir que practicar más allá de lo que he descrito en este capítulo puede profundizar tanto nuestro compromiso que surja un conocimiento claro como parte integral de nuestra meditación. Estamos en el sendero del conocimiento, pero se necesita sobre todo paciencia, y al egocentrismo, que aspirábamos a dejar detrás en el

Mientras San Juan y los Budistas tienen razón al alertarnos en relación con los peligros de apego a los estados alterados de consciencia oa las extraordinarias experiencias, podemos cultivar una orientación saludable, desapegada. El problema potencial es nuestra actitud, y no las experiencias en sí. Es por tanto de suma importancia crear una relación correcta con la experiencia contemplativa, para que no se convierta en una distracción de la meta principal. En particular, uno debería abstenerse de explotar las experiencias o incluso de interpretarlas prematuramente. La actitud más saludable es la de la simple aceptación, tratando tales experiencias como fenómenos inesperados cuyo significado se nos revelará en su momento, pero que no necesitan ser comprendidas inmediatamente. Las experiencias vivenciadas durante la meditación pueden ser novedosas y maravillosas, y podemos observarlas apreciativamente, pero deberíamos abstenernos de hablar de ellas excepto con un profesor, colega o amigo de confianza. En las etapas más avanzadas de la práctica meditativa, el significado se une a la experiencia, pero al principio usualmente no. Con esto quiero decir que practicar más allá de lo que he descrito en este capítulo puede profundizar tanto nuestro compromiso que surja un conocimiento claro como parte integral de nuestra meditación. Estamos en el sendero del conocimiento, pero se necesita sobre todo paciencia, y al egocentrismo, que aspirábamos a dejar detrás en el

primer portal hacia la meditación, no se le debiera permitir que enturbie aquí nuestra visión. Los pormenores de estas prácticas se describirán hacia el final de esta obra.

Mientras que la vida meditativa es diferente para cada persona, los elementos clave son comunes para la mayoría. Como he enfatizado, debemos establecer el fundamento moral correcto para la meditación mediante el cultivo de las actitudes de humildad, reverencia y altruismo. El verdadero fundamento para la vida meditativa es el amor. Una vez que caminamos a través del portal de la humildad, pronto descubriremos el tumulto de nuestra vida interior y la necesidad de ocuparnos de él. Se emprenden ejercicios para controlar y en último término transformar el caos de la mente en un estado de calma y claridad dentro del cual un nuevo sentido del yo –el yo silencioso- puede emerger. No necesitamos esperar a lograr completamente esto (si lo hiciéramos, esperaríamos para siempre) para comenzar a meditar sobre los sublimes pensamientos de las escrituras, los misterios de la naturaleza, nuestra propia constitución humana, o los temas de investigación con los que estamos ocupados. Finalmente, debemos regresar a la vida como seres plenamente encarnados, integrando nuestras experiencias contemplativas en la vida cotidiana, con gratitud por el tiempo y las experiencias que se nos han regalado… y conscientes de que nuestro trabajo en la vida se enriquecerá con ello. Cada día retomamos el paciente trabajo de renovación. Como Thoureau escribió, “Dicen que en la bañera del Rey Tching-thang estaba grabada la siguiente leyenda: 'Renuévate a ti mismo por completo cada día, hazlo una y otra vez, y por siempre de nuevo'”.[23]

Arthur Zajonc

Traducido por Luis Javier Jiménez

Equipo Redacción Revista BIOSOPHIA

[1] Rilke, carta del 12 de agosto de 1904 a Franz Kappus, traducción de Stephen Mitchell, Letters to a Young Poet (Cartas a un Joven Poeta) (New York: Vintage, 1986), p. 87; o en alemán en Von Kunst und Leben, p. 159.

[2] Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence ( Inteligencia Emocional ) (New York: Bantam Books, 1995)

[3] Rudolf Steiner, Die Verbindung zwishen Lebenden und Toten, Gesamtausgabe 168 (Dornach, Suiza: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1995), pp. 94-95.

[4] Rainer Maria Rilke, “ Moderne Lyrik” en Von Kunst und Leben (Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 2001), p. 9 (traducción de Arthur Zajonc).

[5] Thomas Merton, “Love and Solitude”, Love and Living, (“Amor y Soledad”, El Amor y la vida), ed. Naomi Burton y Brother Patrick Hart (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1985).

[6] Arthur Zajonc, “Dawning of Free Communities for Collective Wisdom” (El Amanecer de las Comunidades Libres para la Sabiduría Colectiva”:

http://www.collectivewisdominitiative.org/papers/zajonc_dawning.htm

[7]Marguerite Porete, The Mirror of the Simple Soul in Medieval Writings on Female Spirituality (El Reflejo del Alma Sencilla en los Escritos Medievales sobre la Espiritualidad Femenina), ed. Elizabeth Spearing (New York: Penguin 2002), p. 120 y siguientes.

[8] Rudolf Steiner, Cómo Conocer los Mundos Superiores (Hudson, NY: Editorial Rudolf Steiner, p. 18.

[9] Daniel Goleman, Destructive Emotions (Emociones Destructivas) (New York: Bantam Books, 2003), p. 78; B. Alan Wallace, Tibetan Buddhism from the Ground Up (Budismo Tibetano desde lo Básico) (Boston: Wisdom Publication, 1993), Capítulo 5.

[10] Rudolf Steiner, Cómo Conocer los Mundos Superiores, Editorial Rudolf Steiner.

[11] Martin Luther King Jr. The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr., ed. Clayborne Carson (New York: IPM/Warner Books, 2001), Capítulo 8.

[12] Thomas Merton, reimpreso en Bulletin of Monastic Interreligious Dialogue (Boletín de Diálogo Interreligioso Monástico), nº 67, Agosto de 2001. También online en www.monasticdialog.com/bulletins/67/merton.htm

[13] Juan Ramón Jiménez, herederos de Juan Ramón Jiménez.

[14] El lenguaje nos falla al tratar de describir el no-yo. Como en la teología negativa o la via negativa, los peligros asociados a describir los atributos positivos de un yo superior son insalvables.

[15] Rumi:The Book of Love ( Rumi: El Libro del Amor ), trad. Coleman Barks (New York: Harper Collins, 2003), p. 179

[16]Erwin Schrödinger, What is Life? Mind and Matter (¿Qué es la Vida? Mente y Materia) (Londres: Cambridge University Press, 1967), p. 107.

[17] Stephen Mitchell, The Enlightened Heart (El Corazón Iluminado) (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), p. 5.

[18] Más sobre la ciencia de Goethe en Goethe's Way of Science (La Forma de Ciencia de Goethe), de David Seamon y Arthur Zajonc, (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1998) o The Wholeness of Nature (La Completitud de la Naturaleza), de Henri Bortoft, (Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Press, 1996).

[19] Stephen Mitchell, Tao Te Ching (New York: Harper Collins, 1998), p. 15.

[20] Ralph Waldo Emmerson, “Nature 1836”, Selected Essays (Ensayos Escogidos) editado por Larzer Ziff (New York: Penguin Books, 1992), p. 39.

[21] Salmo 131, La Biblia, editorial Herder, 2005.

[22] San Juan de la Cruz, El Ascenso del Monte Carmelo, Capítulo 23.

[23] Thoreau, Walden and Civil Disobedience (Walden y la Desobediencia Civil), p. 60.

> VISTO EN rebistabiosofia.com